Orthopaedic Surgery is sometimes considered one of the ‘colder’ branches of medicine. Now, this doesn’t mean that Ortho surgeons aren’t inherently hot or anything like that (they fortunately are ![]() ).

).

What it means is that… especially in the eyes of a young house officer… that there’s a lower chance of having your ward patients drop dead while you are having your midnight cup of Milo in the pantry.

So it’s rather unusual that the very first death I witnessed as a house officer, years ago was in my first rotation: orthopaedics.

I remember it clearly. There were two of us in charge of the male orthopaedic ward that week, and one Friday afternoon found me at the foot of the bed of Mr Salleh, a man in his 60s with a distinguished aura about him.

He’d been admitted for gouty arthritis – plain gout, for which we had given him some colchicine, and his toe pain had quickly disappeared. I told him that he could be discharged today, but after a little negotiation, we agreed that he would go home the next morning.

He cracked some long forgotten joke, and I smiled as I turned off to the next bed, leaving Mr Salleh scratching at the gouty swellings on his feet.

The next morning I clocked in just in time and hurried up the stairs to my ward, where the medical officer on call had already started his ward rounds with the whole gang.

Saturday mornings on the orthopaedic wards were some of the most pleasurable days as an intern. After rounds we would all head down to the hospital cafeteria and stuff ourselves silly, then those of us on-call would stroll back to the ward to do some toe amputations, wound cleaning and tick items off the ward to-do-list as we did them.

I stood, clipboard in hand, jotting down the little tasks the medical officer gave us as we advanced through each cubicle. Then we came to Mr Salleh’s bed.

“Mr Salleh, how are you? Ready to go back?”, asked Dr Ching Keng Heong, one of my finest intern colleagues.

Mr Salleh’s wife was sitting on the bedside chair reading a colourful magazine. No one had smartphones back then.

“Dia awal pagi dah takleh tunggu nak balik, doktor,” (He’s been impatient to go home since morning) said the wife, chuckling.

Everyone laughed. Everyone except Mr Salleh.

He lay unusually quiet on the bed. Mrs Salleh put her hand on his shoulder and shook him gently.

“Abang..” she called sweetly. He stayed silent.

“Mr Salleh, wake up.” I reached over and rubbed his chest. His skin felt cold. Dr Ching grasped his wrist.

“Can’t feel his pulse,” he said. We all stood shocked for a moment. Dr Prashant Narhari, the medical officer recovered first.

“Start CPR!” said Dr Prashant.

We sprang into action. I had never actually initiated CPR before, so I rushed to fetch the resuscitation trolley as Dr Tanabalasingam and Dr Randy Koh crawled onto Mr Salleh’s bed, felt for his sternum, and started giving him chest compressions.

Dr Tan Chew Ean and I exposed both Mr Salleh’s thighs to look for large veins to cannulate, and tried in vain to open a route to infuse fluids. The ward nurses strapped him into a cardiac monitor, but there was no sign of life on the screen. Mr Salleh was gone.

His arms and legs were stiff. Rigor mortis is when the muscles gradually harden in the hours after death, so he had likely expired unobserved some hours before.

We took desperate sweaty turns performing chest compressions , while Dr Chin Kai Ning led a wailing Mrs Salleh out beyond the curtains.

Later I sat at the nursing counter, watching as the morgue staff placed Mr Salleh, wrapped in a white sheet, onto a covered steel gurney and wheeled him from the place of death. It turned out he had had a heart attack while it was still dark outside.

It was not my first encounter with death, and Mr Salleh had died long before our feeble attempts to save him, but such was my initiation into the world of the dying as a doctor.

In the months to come my skills developed, both at resuscitating the dying, and at gently informing families that their loved one would return home a hollow shell.

Some families would take it in stride, as the will of God. Others would openly grieve as painful realisation flooded their hearts. Realisation that this was the end.

Sometimes I wished the power of resurrection was mine. That I could make the pain go away. That I could bring smiles back into the dark and colourless world that had come crashing into our ward.

Well, the power to bring the dead back to life, no… but I was given a different power. One just as worthy – the power to sit with the family, and grieve with them.

Originally written on 7 March 2021 at home.

Note: Some names and details have been changed to protect patient privacy.

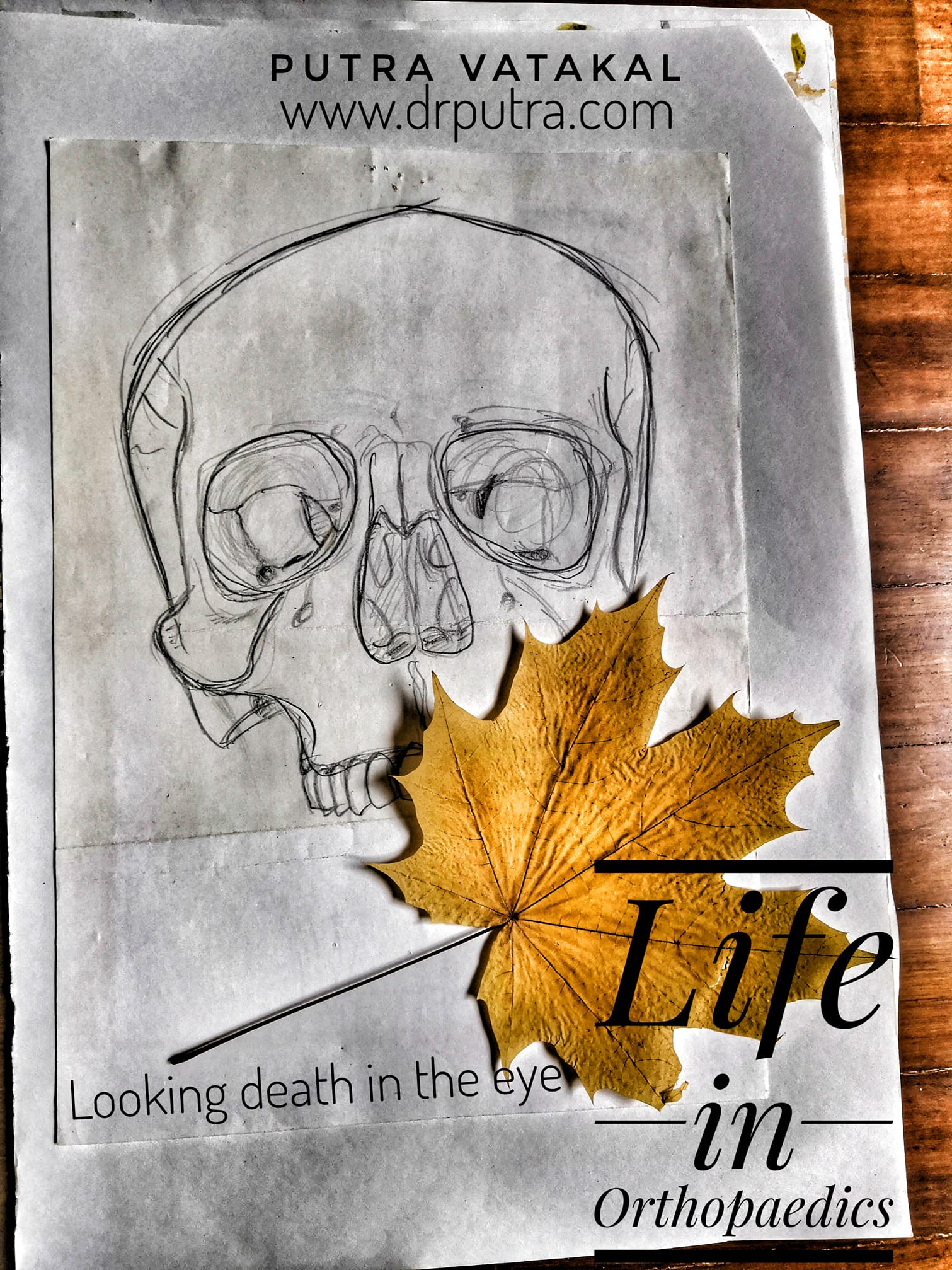

Image notes: Thumbing through old papers from my medical school years, this drawing of a skull I did (trying to impress Chuon Yvonne with my non-existant art skills) caught my eye, and I thought it rather appropriate for a topic just like this one.

We sometimes shy away from the topic of death, but for now at least, where there is life, death will follow – to some, the door to eternal life, to others an unknown mystery. Either way, it’s something significant.